Amazon

Amazon’s Delivery Dilemma: The DoorDash Challenge

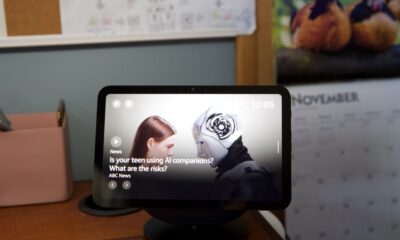

Let’s talk about AI and what I’ve been calling the “DoorDash problem.” This is about to define the next battle in AI, and it might completely transform not only how you order a sandwich — but also how the entire internet economy works in general.

So what, exactly, is the DoorDash problem? Briefly, it’s what happens when an AI interface gets between a service provider, like DoorDash, and you, who might send an AI to go order a sandwich from the internet instead of using apps and websites yourself.

That would mean things like user reviews, ads, loyalty programs, upsells, and partnerships would all go away — AI agents don’t care about those things, after all, and DoorDash would just become a commodity provider of sandwiches and lose out on all additional kinds of money you can make when real people open your app or visit your website.

The DoorDash problem is not specific to DoorDash — it’s just the example I like to use because I think sandwich delivery is a funny proxy for the structure of the global economy. But “who owns the customer?” is a big problem for all of the service companies that came up in what you might call the App Store era: Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Taskrabbit, Zocdoc, you name it.

I’ve been asking the CEOs of these companies about the DoorDash problem on Decoder for months now, because I’ve been predicting that eventually one of them is going to decide it doesn’t want to give up its customers to AI and try to block agents entirely.

Recently, my prediction came true — but it wasn’t a small player that decided to push back against AI; it was one of the biggest players of all. Earlier this month, Amazon sued Perplexity to try and prevent its AI powered Comet browser from shopping on Amazon.com, a move Perplexity has characterized as “bullying.”

So, it’s here: the first major front in the war over who gets to browse the web and who controls the economic experiences of the future has opened up. Now, it’s time for us to really dive deep into the DoorDash problem.

### The sandwich delivery complex

Once upon a time, if you wanted to order a sandwich from your favorite local sandwich shop, you’d actually head over there and order at the counter, or make a phone call directly to the store. It was face-to-face interaction with another human being, and that’s basically what the entire economy looked like, outside of some mail order catalogs and QVC.

The famous dot-com bubble of the late 1990s was fueled by the belief that all of these sorts of interactions would happen on the internet — that instead of going in person or ordering over the phone, you’d visit websites to order sandwiches, or buy pet supplies, or have groceries delivered. The bet was that a huge part of the economy would move to the internet, and the companies that got there first would get huge and make everyone rich.

Looking back, this was broadly the right bet. The problem is that “the internet” in the late 90s looked like desktop browsing on huge tower PCs with CRT displays, accessed over 56K dial-up modems. It was the right idea with the wrong form factor, all way too early. People didn’t actually do all their shopping on those machines, and the bubble popped.

But all of these ideas came back around in the smartphone era, because the smartphone was and remains the perfect form factor for ubiquitous access to the internet. Apple launched the iPhone in 2007 and the App Store in 2008, the same year as Android and what would become the Play Store. The app economy started to actually boom.

Companies like Uber, Airbnb and, yes, DoorDash exploded in popularity, and we really have seen huge chunks of the economy move to the internet because of it. Yes, it took enormous sums of venture capital money, and you might say it was wasteful, but that money was spent, and these services are all huge businesses today. They are so huge, in fact, that spending a bunch of VC money to start another Uber now is a really bad idea — there’s a reason you don’t see that happening. You just can’t do this again on smartphones.

But a lot of the same VCs who funded the smartphone app economy are looking for the next big thing, and they’re backing AI — specifically, agentic AI. We’ve all seen the demos and heard the promises. The bet — the bubble — is that we’ll move the economy yet again, from smartphone apps to AI agents that just do all the work for you. And this isn’t some idea from a few wide-eyed startup founders, although there are definitely a few of those in the mix. Apple, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, OpenAI – they’ve all announced plans for assistants or AI-powered web browsers that would work in this way.

Now, here’s where the problem comes in. That promise of the agentic economy is built on an extremely brittle relationship between the DoorDashes of the world and the AI companies who deploy the agents. It’s not at all clear how things will play out to everyone’s benefit. It is unclear how anyone can prevent this from happening. According to Amazon’s legal complaint, Perplexity repeatedly ignored requests to disable certain functionality and instead chose to disguise its AI agents as human Chrome users and even updated Comet to bypass Amazon’s attempts to stop it.

Amazon is suing Perplexity for violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a significant federal anti-hacking law. Amazon believes that third-party applications like Perplexity should operate transparently and respect the decisions of service providers. Amazon has requested multiple times for Perplexity to remove Amazon from the Comet experience due to the negative impact on the shopping and customer service experience.

In contrast to Amazon’s strong stance, other CEOs seem less concerned about similar issues. For example, Lyft CEO David Risher acknowledges the potential risks of AI agents but believes that existing brand relationships and services will likely prevail over new competitors. Similarly, Zocdoc CEO Oliver Kharraz is confident that established businesses have the expertise and experience to stay ahead of AI-based competitors.

Overall, while some CEOs are unfazed by the potential threat of AI agents, Amazon is taking a proactive approach to protect its business interests. Siri desires to provide various services, but acknowledges that Taskrabbit is essential for this as they have a vast network of Taskers who have been background checked. Siri recognizes that they cannot match Taskrabbit’s network and expertise. The CEOs of ZocDoc and Taskrabbit are confident in their platforms and do not see AI as a threat due to their established services and unique offerings. Uber’s CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, believes in open platforms and is willing to work with AI companies, considering the unique advantages they bring. He emphasizes the importance of focusing on consumer experience first before worrying about economics. This approach aligns with Uber’s philosophy of building the business first and figuring out profitability later. DoorDash also values the end-to-end experience they provide, focusing on personalization, reviews, fulfillment, and support rather than just order placement channels. A channel would need to replicate all of our end-to-end functionality in order to fully serve a customer. Each time we have integrated with partner properties, we have experienced faster growth at a larger scale.

Tony, I would love to have you on the show to delve deeper into this idea. I recently heard a more detailed version of this concept from Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky, one of my favorite guests on Decoder. Chesky expressed his belief that no single company can build all interfaces for everything. He highlighted the problems with the AI maximalist view and emphasized the importance of companies maintaining a relationship with their customers.

Various industry leaders, including Sundar Pichai and Kevin Scott, have emphasized the need for business sense in the development of AI agents. They have compared the situation to brands and retailers taking cuts from transactions and highlighted the importance of making the economics work.

Despite these pragmatic viewpoints from smaller players and industry giants, Amazon, a major retail player, has taken an aggressive stance against AI agents. This move raises questions about why Amazon, with its significant presence in the retail market, is leading the charge against AI agents. It is speculated that Amazon, with its extensive ad business, lucrative Prime subscription service, and widespread shopper base, stands to lose the most from AI agents disrupting its operations. Additionally, Amazon’s reliance on habit and its potential vulnerability to replacement make it a target for AI disruption.

In conclusion, the debate surrounding AI agents and their impact on businesses continues to evolve, with Amazon’s aggressive stance bringing new perspectives to the discussion. Many companies invest heavily in marketing and advertising on platforms like Amazon, which has become a significant part of its revenue stream and the overall advertising industry. Amazon’s advertising revenue has been steadily increasing, reaching $17.7 billion in its most recent quarter and projected to surpass $60 billion by 2025. This places Amazon as the third-largest player in the tech advertising space, behind only Google and Meta.

However, the rise of AI agents poses a threat to Amazon’s advertising business model. If AI agents handle shopping tasks on behalf of users, they may bypass traditional advertising methods, making paid placements less effective. This could potentially impact Amazon’s revenue from advertising and its status as a leading online retailer.

To address this challenge, Amazon has developed its own AI shopping assistant, Rufus, and is testing an AI bot called “Buy For Me” to facilitate purchases on third-party websites. By integrating AI technology into its platform, Amazon aims to maintain its relationship with customers and remain a dominant player in the e-commerce market.

Despite these efforts, the emergence of companies like Perplexity, which openly challenge Amazon’s terms of service, poses a unique legal and competitive threat. Perplexity’s approach of prioritizing user experience and innovation over traditional norms has led to clashes with major players in the industry, including Amazon. In the face of legal challenges, Perplexity remains steadfast in its mission to revolutionize the internet and create a more user-centric online environment. The argument presented is that an AI agent acts as an extension of the user, with the same permissions and working solely on the user’s behalf. Perplexity, however, believes that its agents should have access to websites without needing explicit permission. The blog post ends with a defiant statement asserting that users demand efficient shopping experiences, and Perplexity demands the right to offer it.

The author expresses uncertainty about the implications of this situation and invites readers to share their thoughts. They emphasize the importance of ensuring fair compensation for the human labor behind these AI services, highlighting the potential consequences of neglecting the workforce in favor of automation. The article concludes by stressing the need for companies to consider the impact of AI investments on workers’ livelihoods. We are committed to thoroughly reviewing each and every email we receive! Subscribe to Decoder with Nilay Patel, a podcast from The Verge that delves into significant concepts and challenges. Stay updated on similar topics and authors by following them, and receive email notifications. Follow Nilay Patel, AI, Amazon, Decoder, Podcasts, Tech, and Web to enhance your personalized homepage feed and receive daily email digests. These topics cover a wide range of subjects and will keep you informed and engaged. “Can you please pass me the salt?”

into a polite request.

“Could you kindly pass me the salt, please?” Transform the following:

Original: “I am going to the store to buy some groceries.”

Transformed: “To buy some groceries, I am going to the store.” ” I am going to the store to buy some groceries”

into

“I will be heading to the store to purchase some groceries.”

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoEU Takes Action Against Instagram and Facebook for Violating Illegal Content Rules

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoWarning: Facebook Creators Face Monetization Loss for Stealing and Reposting Videos

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoFacebook Compliance: ICE-tracking Page Removed After US Government Intervention

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoInstaDub: Meta’s AI Translation Tool for Instagram Videos

-

Facebook2 months ago

Facebook2 months agoFacebook’s New Look: A Blend of Instagram’s Style

-

Facebook2 months ago

Facebook2 months agoFacebook and Instagram to Reduce Personalized Ads for European Users

-

Facebook2 months ago

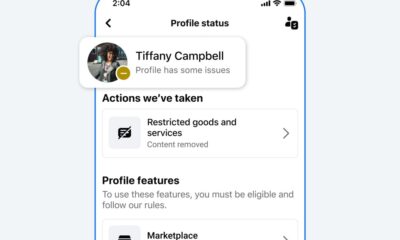

Facebook2 months agoReclaim Your Account: Facebook and Instagram Launch New Hub for Account Recovery

-

Apple4 months ago

Apple4 months agoMeta discontinues Messenger apps for Windows and macOS