Security

Unraveling the Mystery: Inside the Qilin Ransomware Attack

Written by Lindsey O’Donnell-Welch, Ben Folland, Harlan Carvey of Huntress Labs.

A big part of a security analyst’s everyday role is figuring out what actually happened during an incident. We can do that by piecing together breadcrumbs–whether that’s through logs, antivirus detections, and other clues–that help us understand how the attacker achieved initial access and what they did after.

However, it’s not always cut and dry: sometimes there are external factors that limit our visibility. The Huntress agent might not be deployed across all endpoints, for example, or the targeted organization might install the Huntress agent after a compromise has already occurred.

In these cases, we need to get creative and look at multiple data sources in order to determine what actually happened.

Recently, we analyzed an incident where both of the above factors were true: on October 11, an organization installed the Huntress agent post-incident, and initially on one endpoint.

When it comes to visibility, this incident was less about looking through a keyhole, and more akin to looking through a pinhole. Even so, Huntress analysts were able to derive a great deal of information regarding the incident.

The Qilin incident: What we started with

The Huntress agent was installed on a single endpoint following a Qilin ransomware infection. What does that mean from the perspective of an analyst trying to figure out what happened?

We had limited clues to start: there was no endpoint detection and response (EDR) or SIEM telemetry available, and Huntress-specific ransomware canaries weren’t tripped. Because we were also on one endpoint, our visibility was limited to the activity that had occurred on that specific endpoint within the broader environment’s infrastructure.

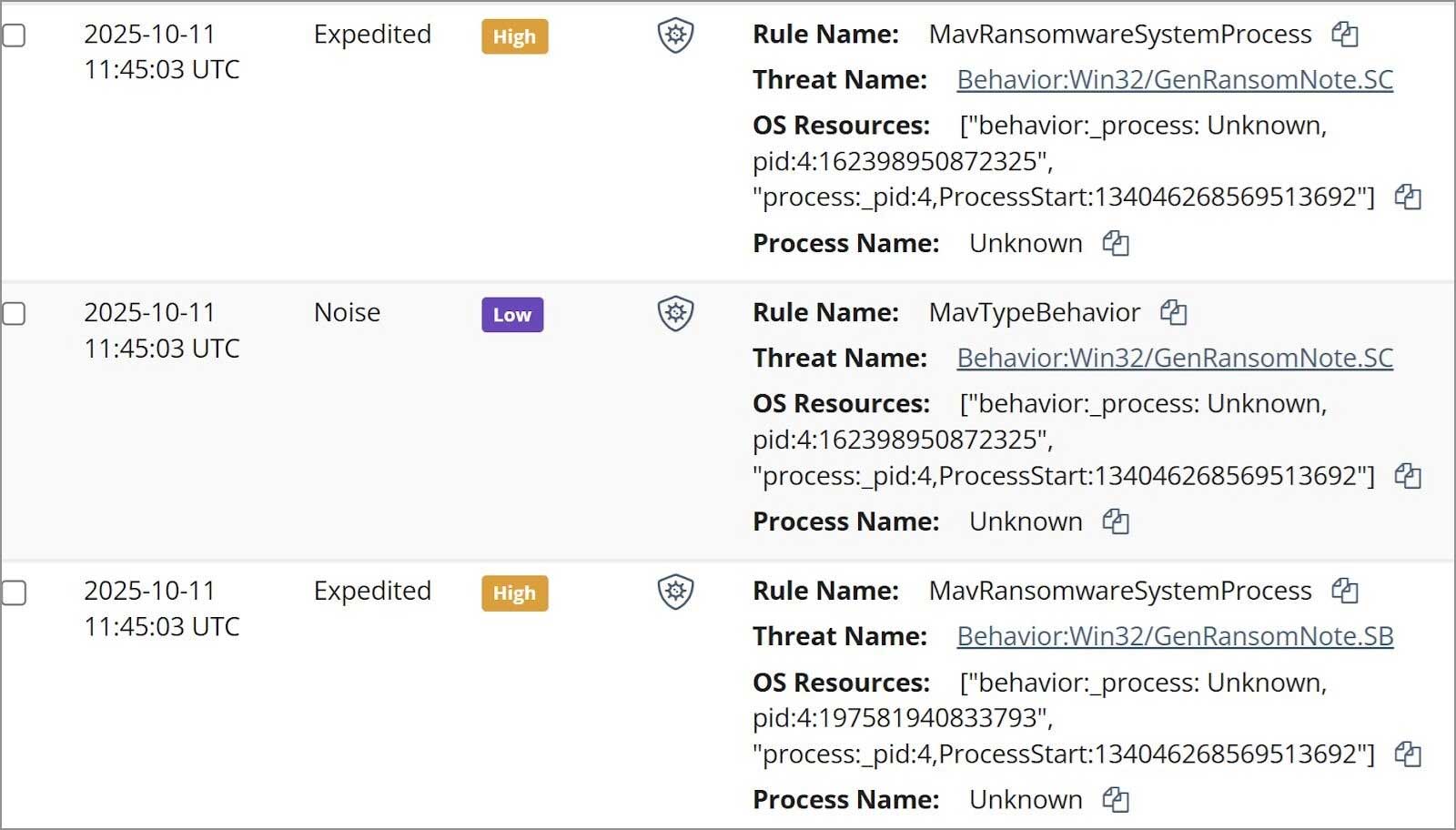

As a result, all Huntress analysts had to start with to unravel this incident was the managed antivirus (MAV) alerts. Once the Huntress agent was added to the endpoint, the SOC was alerted to existing MAV detections, some of which are illustrated in Figure 1.

Preparing for CMMC Level 2 certification doesn’t have to be overwhelming.

Huntress provides the tools, documentation, and expert guidance you need to streamline your audit process and protect your contracts. Let us help you achieve compliance faster and more affordably.

Learn More

Analysts began tasking files from the endpoint, starting with a specific subset of the Windows Event Logs (WEL).

From those logs, analysts could see that on 8 Oct 2025, the threat actor accessed the endpoint and installed the Total Software Deployment Service, as well as a rogue instance of the ScreenConnect RMM, one that pointed to IP address 94.156.232[.]40.

Searching VirusTotal for the IP address provided the insight illustrated in Figure 2.

![Figure 2: VirusTotal response for the IP address 94.156.232[.]40](https://www.bleepstatic.com/images/news/security/h/huntress-labs/qilin-investigation/virustotal.jpg)

An interesting aspect of the installation was that LogMeIn was apparently legitimately installed on the endpoint on 20 Aug 2025 from the file %user%\Downloads\LogMeIn.msi.

Then, on 8 Oct, the rogue ScreenConnect instance was installed from the file C:\Users\administrator\AppData\Roaming\Installer\LogmeinClient.msi.

Further, the timeline indicates that on 2 Oct, the file %user%\Downloads\LogMeIn Client.exe was submitted by Windows Defender for review, and no other action was taken after that event.

Pivoting from the ScreenConnect installation to ScreenConnect activity events within the timeline of activity, analysts saw that on 11 Oct, three files were transferred to the endpoint via the ScreenConnect instance; r.ps1, s.exe, and ss.exe.

Digging in a bit deeper, only r.ps1 was still found on the endpoint (shown below).

$RDPAuths = Get-WinEvent -LogName

'Microsoft-Windows-TerminalServices-RemoteConnectionManager/Operational'

-FilterXPath @'

<QueryList><Query Id="0"><Select>

*[System[EventID=1149]]

</Select></Query></QueryList>

'@

# Get specific properties from the event XML

[xml[]]$xml=$RDPAuths|Foreach$_.ToXml()

$EventData = Foreach ($event in $xml.Event)

# Create custom object for event data

New-Object PSObject -Property @

TimeCreated = (Get-Date ($event.System.TimeCreated.SystemTime) -Format 'yyyy-MM-dd hh:mm:ss K')

User = $event.UserData.EventXML.Param1

Domain = $event.UserData.EventXML.Param2

Client = $event.UserData.EventXML.Param3

$EventData | FT

Based on the contents of the script, it would appear that the threat actor was interested in determining IP addresses, domains, and usernames associated with RDP accesses to the endpoint.

However, the Windows Event Log contained a Microsoft-Windows-PowerShell/4100 message stating:

Error Message = File C:\WINDOWS\systemtemp\ScreenConnect\22.10.10924.8404\Files\r.ps1 cannot be loaded because running scripts is disabled on this system.

This message was logged within 20 seconds of the script being transferred to the endpoint, and the threat actor attempting to run it.

Parsing through PCA logs

The other two files, s.exe and ss.exe, took a bit more work to unravel, because they were no longer found on the endpoint.

However, Huntress analysts were able to take advantage of data sources on the Windows 11 endpoint, specifically the AmCache.hve file and the Program Compatibility Assistant (PCA) log files to obtain hashes for the files, and to see that while the threat actor had attempted to execute the files, both apparently failed.

The threat actor disabled Windows Defender, which were seen in Windows Defender event records, starting with event ID 5001, indicating that the Real-Time Protection feature was disabled. This was followed by several event ID 5007 records, indicating that features such as SpyNetReporting and SubmitSamplesConsent had been modified (in this case, disabled), as well as SecurityCenter messages indicating that Windows Defender had entered a SECURITY_PRODUCT_STATE_SNOOZED state.

The threat actor then attempted to launch s.exe, which was almost immediately followed by the message “Installer failed” in the PCA logs. Based on the identified VirusTotal detections shown in Figure 3, and the behaviors identified by VirusTotal, this file appears to be an infostealer.

The messages in the PCA logs provide indications that the file, identified as an installer, failed to execute.

Seven seconds later, the threat actor attempted to run ss.exe, which was immediately followed by the legitimate Windows application, c:\windows\syswow64\werfault.exe, being launched.

“` The sequence of events observed in the investigation revealed that the PCA logs recorded three consecutive instances of “PCA resolve is called, resolver name: CrashOnLaunch, result: 0” in relation to the ss.exe application, indicating that the application failed to launch.

Before attempting to run the aforementioned files, the threat actor disabled Windows Defender at 2025-10-11 01:34:21 UTC, leading to the Windows Defender status being reported as SECURITY_PRODUCT_STATE_SNOOZED. Subsequently, at 2025-10-11 03:34:56 UTC, the threat actor remotely accessed the endpoint. Shortly after, at 2025-10-11 03:35:13 UTC, multiple Windows Defender detections were triggered for attempts to create ransom notes (Behavior:Win32/GenRansomNote), with subsequent remediation attempts failing.

Following these events, the Windows Defender status was restored to SECURITY_PRODUCT_STATE_ON. The detection by Windows Defender, combined with the remote login, suggests that the ransomware executable was launched from another endpoint, likely targeting network shares.

The investigation also uncovered a Qilin ransom note on the endpoint, shedding light on the ransomware variant involved. Qilin ransomware is classified as a “ransomware-as-a-service” (RaaS) variant, indicating that the ransomware operations are centrally managed, while individual affiliates may employ different attack strategies, leaving behind distinct traces.

The use of multiple data sources proved invaluable in piecing together the threat actor’s activities. Despite the limited visibility provided by the post-incident installation of the Huntress agent, analysts were able to gain a deeper understanding of the incident progression. This comprehensive approach not only validated findings but also offered a clearer depiction of the events that transpired.

By cross-referencing data across various sources, analysts were able to uncover the threat actor’s tactics, such as the use of a rogue ScreenConnect instance for deploying malicious files. This holistic approach ensures a more accurate assessment of malicious activities and serves as a foundation for effective decision-making and remediation efforts.

In conclusion, the investigation highlights the importance of leveraging multiple data sources to gain a comprehensive understanding of security incidents. By validating findings across different sources, organizations can better respond to threats and make informed decisions to enhance their security posture.

For organizations seeking to enhance their security measures, Huntress offers a range of innovative solutions. Through continuous innovation and a commitment to protecting businesses from cyber threats, Huntress aims to empower organizations to safeguard their digital assets effectively.

To learn more about Huntress and its security solutions, consider attending the upcoming webinar to gain insights into the latest cybersecurity trends and best practices. Reserve your spot now to stay ahead of evolving threats and protect your organization from potential security risks.

—

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs):

– Rogue ScreenConnect instance ID: 63bbb3bfea4e2eea

– s.exe hash: af9925161d84ef49e8fbbb08c3d276b49d391fd997d272fe1bf81f8c0b200ba1

– ss.exe hash: ba79cdbcbd832a0b1c16928c9e8211781bf536cc

– Ransom note: README-RECOVER-

This article is sponsored and written by Huntress Labs. Transform the following statement:

“I am going to the store to buy groceries.”

into a question.

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoEU Takes Action Against Instagram and Facebook for Violating Illegal Content Rules

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoWarning: Facebook Creators Face Monetization Loss for Stealing and Reposting Videos

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoFacebook Compliance: ICE-tracking Page Removed After US Government Intervention

-

Facebook4 months ago

Facebook4 months agoInstaDub: Meta’s AI Translation Tool for Instagram Videos

-

Facebook2 months ago

Facebook2 months agoFacebook’s New Look: A Blend of Instagram’s Style

-

Facebook2 months ago

Facebook2 months agoFacebook and Instagram to Reduce Personalized Ads for European Users

-

Facebook2 months ago

Facebook2 months agoReclaim Your Account: Facebook and Instagram Launch New Hub for Account Recovery

-

Apple4 months ago

Apple4 months agoMeta discontinues Messenger apps for Windows and macOS